Real Estate Tokenization in Qatar (2026): what works, what breaks, and when it makes sense

In Qatar, tokenization isn’t a blockchain choice — it’s a legal one. Learn what rights a real estate token can represent, what remains off-chain (registry, cashflows, property management), and how to design the model so on-chain transfers stay aligned with real-world enforcement.

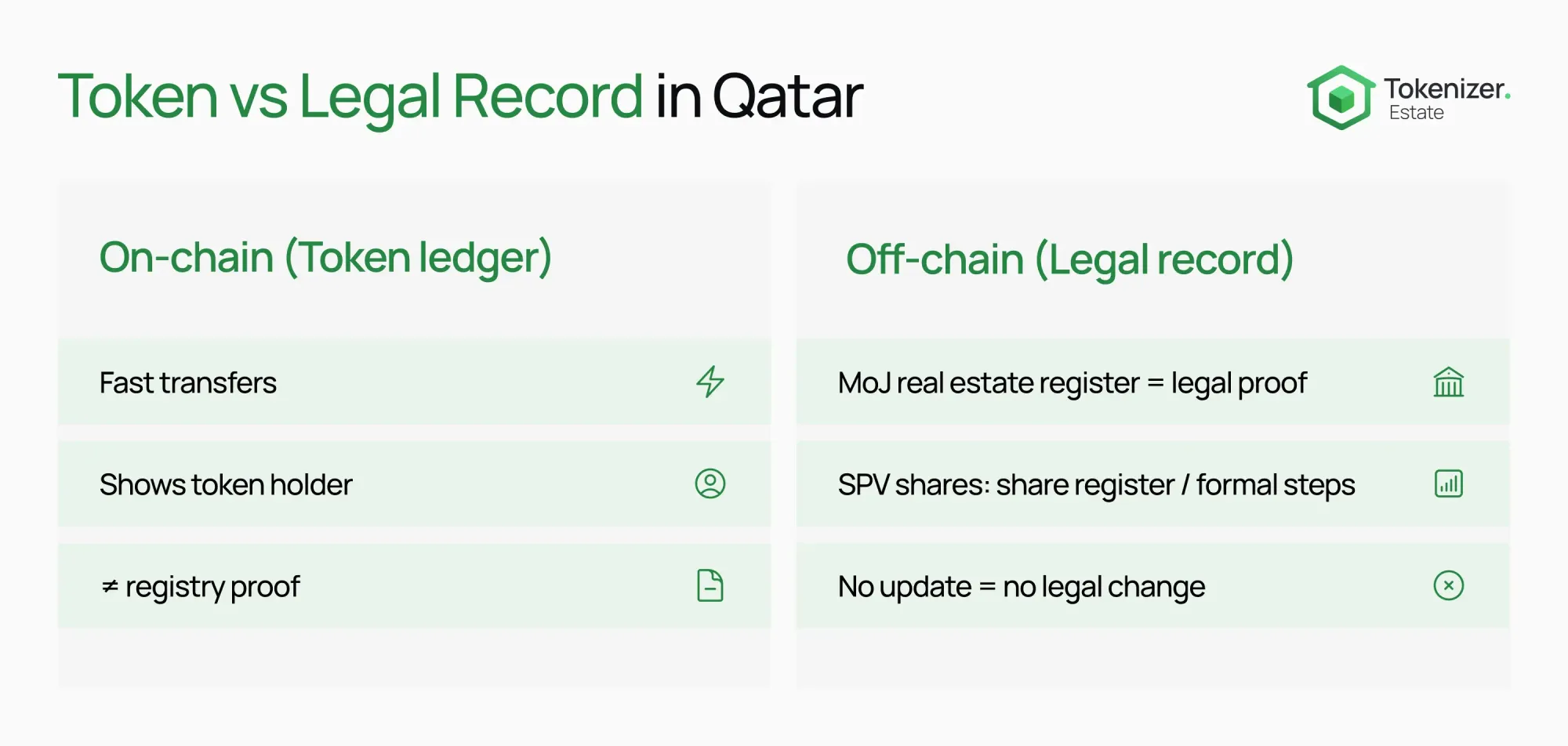

Real estate tokenization in Qatar is not mainly a “blockchain” choice. It is a choice about what legal right you put into a token, which off-chain record proves it, and what happens when something goes wrong.

After reading this article, you will understand the real limits of real estate tokenization in Qatar: what the token really represents, what still stays off-chain (registries, money flows, property management), and what usually breaks when legal records and on-chain transfers do not match.

Real Estate Tokenization in Qatar 2026

Tokenization means you take an existing legal right and represent it with a token. Holding and transferring the token is meant to track who holds that right. In practice, the right can be a share in a company that owns the property, a long lease/usufruct right, or a contractual claim like a rent-linked entitlement.

What tokenization can do well is make holding, transfer, and admin easier to run as a digital process. This matters once you want to reach more investors (including cross-border interest), handle smaller tickets, or manage many holders without a heavy manual back office.

What tokenization does not do is replace the legal steps that move ownership or create enforceable rights outside the token system. In Qatar, core proof and enforcement still sit with registries, contracts, and courts.

If you want the “why people do this” side (global access, fractional size, admin efficiency) in plain language, benefits overview lists the common upside claims—just keep the Qatar constraints below in mind.

QFC rules: which tokens are allowed (and which are not)

In Qatar, the QFC Digital Asset Regulations matter because they define what a token is in legal terms, and how ownership and transfer work for a “permitted token.”

A useful practical point: under the QFC framework, transfer is tied to control over the power to transfer the token. That can make token transfer clean and fast inside the token system. It also means key custody and access control are not side topics—they are part of how “ownership” is treated in practice.

But the same framework also draws boundaries. Some tokens are “excluded tokens,” including tokens that act as a substitute for currency or can be used as a means of payment (stablecoins are an example in the framework). Token services carried on in or from the QFC cannot be provided “in relation to” excluded tokens. This matters once your product design assumes token-based settlement or payouts are “just plumbing.”

There is also a licensing split teams often discover late. Token services (like custody, exchange operation, and transfer services) require licensing, and activity connected to “investment tokens” can also trigger regulated activity approval/authorisation. So “we built a platform” can quickly become “we run a regulated operating model.”

QFC Digital Asset Regulations define permitted tokens, excluded tokens, token services, and court remedies.

This matters once you promise “instant settlement” or “automatic payouts.” The constraint is rarely the smart contract. The constraint is whether your token model stays inside the permitted category and whether your service roles are properly licensed.

What stays off-chain: registry, ownership rules, and eligibility

The hard limit is still the underlying right. Even if your token transfer is clean, you must ask: what real-world record proves the right, and how is it updated?

Qatar’s real estate registration regime has moved toward digital processes (electronic documents and transactions can carry legal effect under the newer framework, as described in published legal commentary). That helps speed and admin. It does not remove the need to register the right where registration is required, and it does not make token transfer itself the real estate register.

Foreign ownership and use rules add another layer of realism. Qatar’s official instruction manual describes designated areas for non-Qatari ownership or usufruct, and it describes usufruct terms up to 99 years. It also includes numeric thresholds tied to residency outcomes: more than QAR 730,000 for real estate residency and more than QAR 3,650,000 for residency with permanent-residency privileges.

Official instruction manual lists the 99-year usufruct concept, area counts, residency thresholds, a four-year build condition for vacant land, and the 0.25% registration fee in case of sale.

This matters once you plan secondary transfers. Tokenization can widen investor outreach, but only if you can keep eligibility and ownership/use constraints aligned with who can actually hold the token over time.

Where projects usually break (and how to design around it)

Most projects fail because tokens trade faster than the legally enforceable record can follow. The result is a gap between “who the token ledger says is the holder” and “who the legal system recognizes as entitled,” especially when money, control, or default forces the question.

This usually surfaces in three moments.

First, secondary trading. Liquidity sounds like the reason to tokenize, but liquidity only exists if you have a compliant and usable venue and a clear method for keeping eligibility rules intact during transfers. If you cannot keep KYC and eligibility aligned with token ownership, restricted holders can enter through the back door. That turns a product issue into a compliance issue.

Second, distributions. If your token is linked to rent or profit, smart contracts do not verify rent rolls, expenses, or reserve choices. Automation pays out fast, but it can also spread errors fast. This is why teams discover too late that the real bottleneck is data quality, auditability, and dispute handling—not the payout code.

Third, governance and stress. Real estate forces decisions: refinancing, sale timing, disputes, major capex, manager replacement. A dispersed token holder base can struggle to decide quickly, and the cost of delay is real. This usually appears mid-life, not on day one.

A practical way to reduce these failure risks is to treat “off-chain + on-chain” as one operating system, not as separate tools. Many teams use a platform approach so investor eligibility, records, and distributions are not held together by ad hoc spreadsheets; cost guide breaks down the cost categories that usually show up when you make this real.

Do real estate tokenization in Qatar only when the token is tightly mapped to an enforceable off-chain right and you can keep registry steps, eligibility rules, and reporting aligned over time; otherwise, do not ship a token.

Conclusion

Tokenization in Qatar is not fundamentally different from anywhere else: it works when you approach it as a structured legal and operating model, not just a smart-contract feature.

If the token is clearly mapped to an enforceable off-chain right, and you keep registry steps, eligibility/KYC, reporting, and distributions consistently aligned with token ownership, tokenization can run smoothly and deliver what people actually want from it: broader access, simpler administration, and more efficient processes.

So the takeaway is straightforward: approach real estate tokenization with a clear legal design, a disciplined operating setup, and the right compliance foundation — and it will work as intended.