Real Estate Tokenization in the Netherlands 2026

In the Netherlands, tokenization is a legal-mapping problem: what right sits in the token, which off-chain register proves it, and how transfers work. This 2026 guide covers Kadaster/notary limits, BV/NV & STAK structures, AFM thresholds, and common failure points.

Real estate tokenization in the Netherlands in 2026 is not mainly a “blockchain” choice. It is a choice about what legal right you are putting into a token, who controls the legal record, and what happens when things go wrong.

This article is for founders who want to ship a tokenized real estate product, asset owners and managers who consider a digital issuance, and investors who need to judge if a Dutch tokenized deal is real and enforceable. It helps with a practical decision: do we do tokenization at all, and if yes, what scope is still safe to run in real life.

If you want a simple product view of how tokenization projects are usually built step by step, here is a short overview of the typical process (without going deep into the legal limits in the Netherlands).

Real Estate Tokenization in the Netherlands 2026

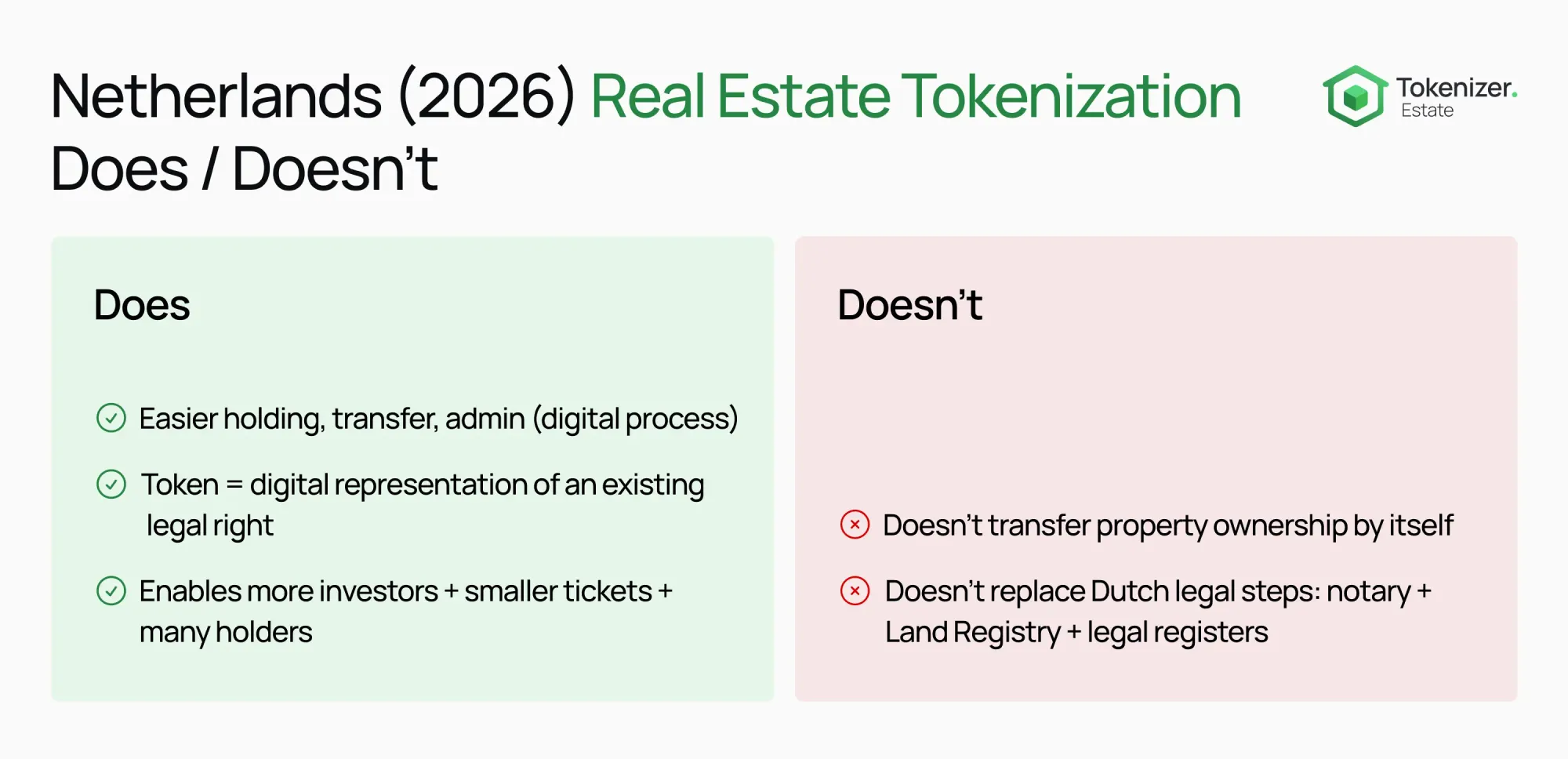

Tokenization means you take an existing legal right and represent it with a token, so holding and transferring the token is meant to track who holds that right. The right can be a share in a company that owns the property, a depositary receipt issued by a STAK, or a contractual claim like a loan or cashflow entitlement.

What tokenization does well is make holding, transfer, and administration easier to run as a digital process. This matters once you want to reach more investors, handle smaller tickets, or manage many holders without a heavy manual back office.

What tokenization does not do is replace the Dutch legal steps that actually move ownership or create enforceable rights. In the Netherlands, those steps still sit with the notary, the Land Registry, and the relevant legal registers.

If you want the “why people do this” side (including global investor reach and fractional access) in plain language, benefits article outlines the usual upside claims—just keep in mind the Dutch constraints below.

Kadaster and notary limits in Dutch real estate tokenization

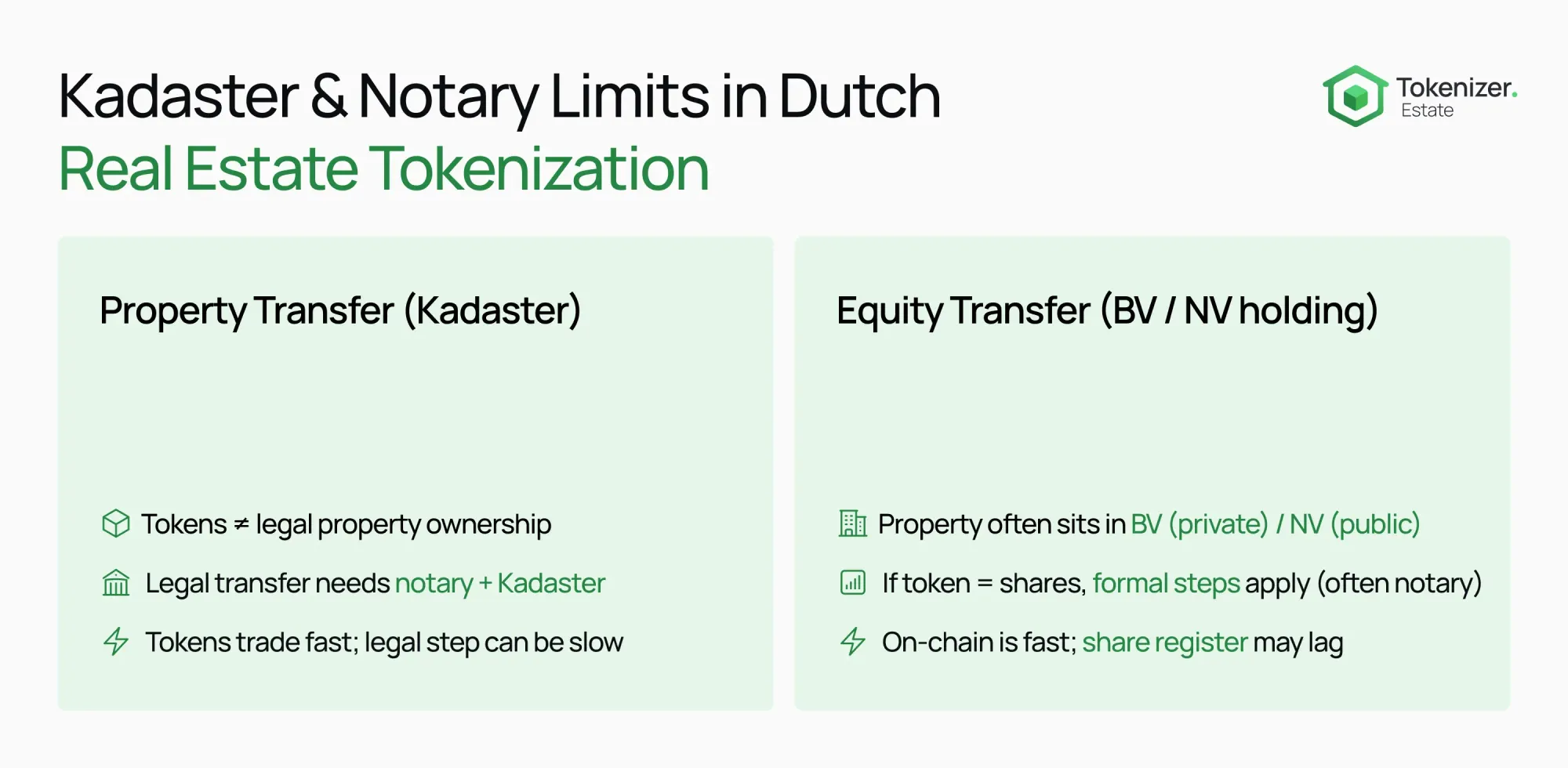

The first hard limit is property ownership. In the Netherlands, legal ownership of real estate moves when a civil-law notary registers a notarial transfer deed in the Land Registry (Kadaster). A token transfer does not update the Kadaster record, and it does not create legal delivery by itself. For the clean source statement, Kadaster explains that recording the notarial deed is the mandatory step for a change in the legal status of registered property.

This matters once you promise “instant settlement” or fast secondary trading. You can still trade tokens, but you need a clear rule for what the token trade actually means. Is it only an economic position? Is it a promise to complete the off-chain legal step later? Or is it blocked until the off-chain register is updated? If this is not defined early, customer expectations can change, timelines can slip, and liability can increase.

The second limit is equity transfer in common Dutch holding structures. If your token represents shares in a Dutch BV (Besloten Vennootschap — a private limited company) or NV (Naamloze Vennootschap — a public limited company) that owns the property, share transfers have their own formal steps (often including a civil-law notary). So even if your on-chain transfer is fast, the legally effective share ownership can lag unless you create a strict link between token ownership and the official share record.

This is why many “real estate token” products quietly become one of two things in practice:

- A structure where legal control stays concentrated (for example through a STAK), while the token gives economic exposure.

- A structure where the token represents a contractual claim (loan, profit share, rent-linked entitlement), so you avoid pretending the token is property title.

Both models can work, but they offer different rights and come with different risks.

To make the link between token holders and real-world rights manageable, many teams choose a platform approach where off-chain registers, investor eligibility, and distributions are handled as an operational system, not as ad hoc spreadsheets. If you want to see how a platform frames that operational layer, Tokenizer.Estate platform describes the kind of modules teams often use to keep admin consistent.

Regulation and compliance boundaries for tokenized real estate in the Netherlands

In 2026, the most common regulatory mistake is not “forgetting crypto rules.” It is misreading what the token is in legal terms.

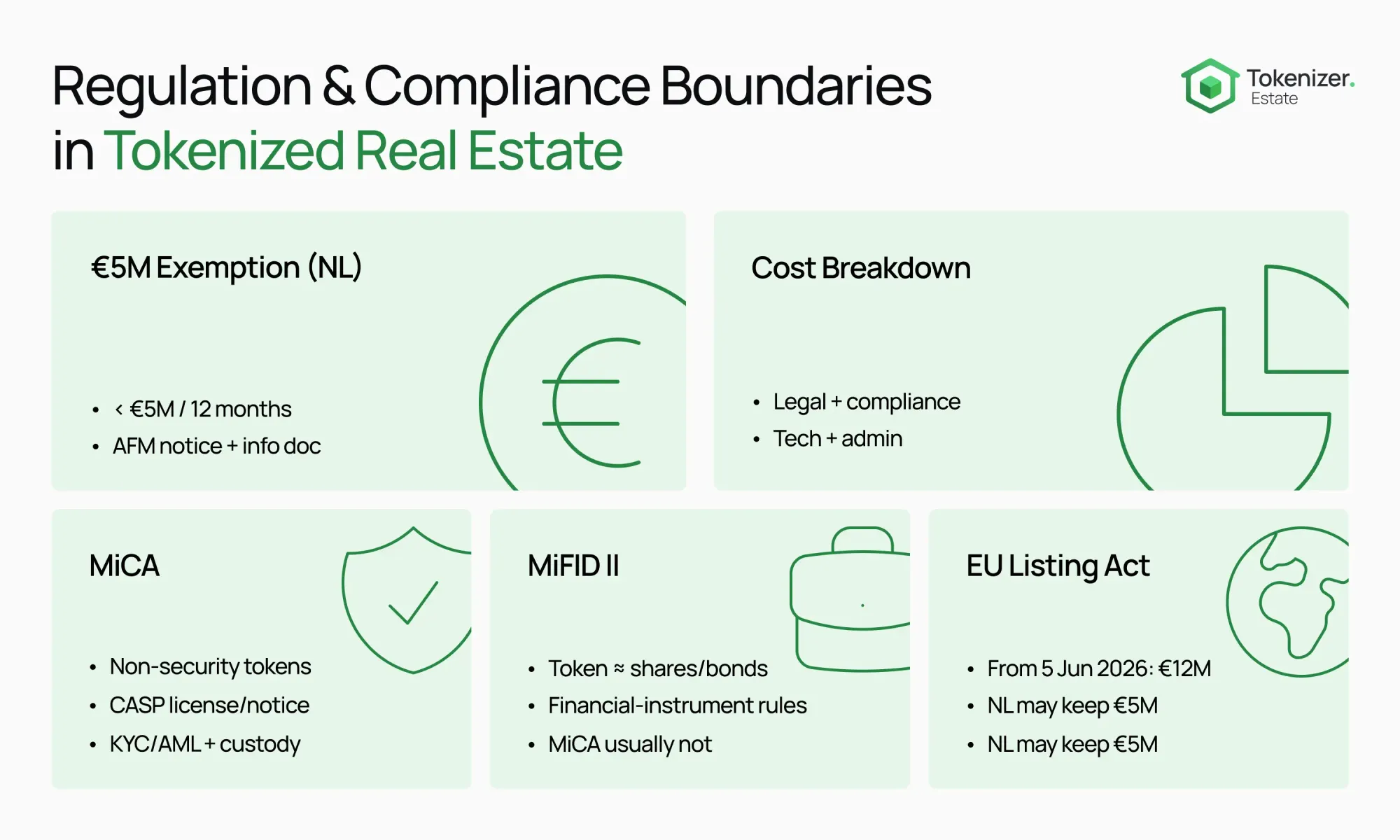

If the token grants rights equivalent to shares or bonds, it can be treated as a MiFID II financial instrument (in substance). That classification affects how it can be offered, traded, and settled. Separately, MiCA applies from 30 December 2024, and crypto-asset services can require licensing/notification. These layers can stack in messy ways, especially when a product looks like both a “token service” and a “securities offer.”

A very practical Dutch boundary is the prospectus regime. In the Netherlands, there is a well-known prospectus exemption up to €5 million total consideration over 12 months, but it is not “do whatever you want.” It comes with conditions, including notifying the AFM in advance and providing an information document to investors. For the primary wording, AFM explains the €5 million exemption and its conditions.

This matters once you plan a raise in “small rounds.” The €5 million threshold is calculated over a 12-month window and can include offers across a group, so poor planning can push you over the line after you have already built your structure and marketing plan.

Also, from 5 June 2026, the EU Listing Act raises the default EU prospectus-exemption threshold to €12 million over 12 months (with an option for Member States to set €5 million instead). That does not remove legal work, but it can change when a full prospectus becomes a gating cost.

If your team needs to budget the non-obvious parts (legal, compliance, tech, ongoing admin), cost guide breaks down the categories that usually show up—use it as a planning map, not as a promise of what your project will cost.

Where tokenized real estate projects break—and how to scope them so they don’t

Most projects fail because tokens trade faster than the legally enforceable record can follow. The result is a gap between “who the token ledger says is the holder” and “who the legal system recognizes as entitled,” especially when money, control, or default forces the question.

This usually surfaces in three moments:

First, secondary trading: Liquidity sounds like the reason to tokenize, but liquidity only exists if you have a compliant and usable venue and a clear method for keeping eligibility rules intact during transfers. If you cannot keep KYC/eligibility aligned with token ownership, restricted investors can become holders through the back door. That turns a product problem into a compliance problem.

Second, distributions: If your token is linked to rent or profit, smart contracts do not verify rent rolls, expenses, or allocation choices. Automation pays out fast, but it can also spread errors fast. This is why teams discover too late that the real bottleneck is data quality, auditability, and dispute handling—not the payout code.

Third, governance and stress: Structures that separate economic rights from legal control can be operationally stable in calm markets, but they create sharp edges in stress: refinancing, asset sale timing, disputes, or underperformance. If holders thought they were buying “ownership control” but really bought “economic exposure,” the conflict tends to appear mid-life, not on day one.

Tokenization does have real positives when scoped correctly: it can widen investor outreach, including cross-border interest, because digital access and smaller participation sizes are easier to operationalize. But this only helps if your product can legally and operationally support those investors, and if you can keep transfer restrictions, registers, and reporting consistent over time.

Conclusion

Do real estate tokenization in the Netherlands in 2026 only when the token is tightly mapped to the enforceable off-chain record (Kadaster or a legally maintained register), and your business case still works without assuming guaranteed secondary-market liquidity.

The decision moment is usually a founder’s go/no-go on whether to promise liquidity, an issuer’s choice between tokenized equity versus tokenized claims, or an investor’s diligence question: “If something goes wrong, what exact record proves my right, and who can enforce it?” If you can answer that clearly before launch, tokenization becomes a controlled operating model. If you cannot, it becomes a mismatch that shows itself later—when changing course is expensive and often irreversible.