Tokenization in Poland 2026: legal records, MiCA timing, and what works in real life

Tokenization in Poland can streamline investor access and admin, but legal records still rule. Learn what tokens really represent, why notaries and registers matter, how MiCA vs MiFID II changes the perimeter, and where projects break in practice.

Tokenization in Poland is getting serious attention for a simple reason: it can make investing and fundraising easier to run as a digital process. When it is scoped well, it can help you reach more investors (including cross-border interest), support smaller ticket sizes, and reduce manual admin for many holders.

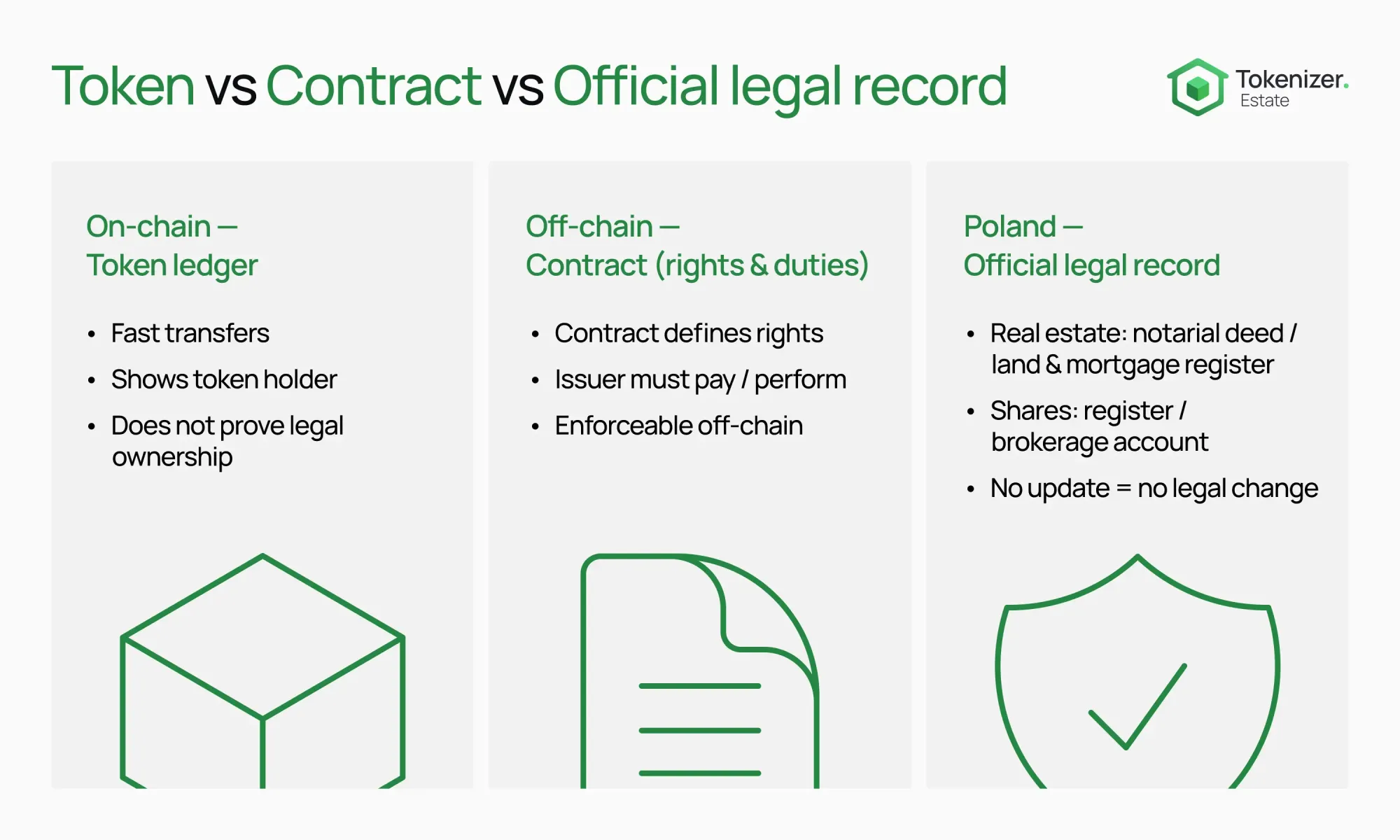

But Poland is also a place where “token ownership” often meets a hard boundary: the legal record that actually proves a right is usually off-chain. So the real question is not “which blockchain?” It is: what right sits in the token, who controls the legal record, and what happens when something goes wrong.

After reading this article, you will see the real boundaries of tokenization in Poland: what the token represents, what stays off-chain, and what usually fails when legal records and on-chain transfers don’t match

Tokenization in Poland 2026: what the token really represents

Tokenization means you take an existing right and represent it with a token, so holding and transferring the token is meant to track who holds that right.

The right can be a share in a company, a debt claim, or a contract right to cashflows. The token can make holding, transfer, and administration easier to run. This matters once you want to reach more investors, handle smaller tickets, or manage many holders without a heavy back office.

What tokenization does not do is replace the Polish legal steps that move ownership or create enforceable rights. In practice, you always have an “off-chain truth” somewhere: a notarial deed, a shareholder register, a creditor relationship, or a contract with an obligor.

If you want the upside case in plain language (including global investor access), benefits article lists. In Poland, those positives only matter if you can keep the token, the legal record, and investor eligibility aligned.

Real estate tokenization in Poland: the notary and land-title limit

The first hard limit is property ownership. In Poland, the Civil Code requires a notarial deed for an agreement that obliges the transfer of ownership of real estate, and also for the agreement that transfers ownership.

This matters once you promise “instant settlement” for a property deal. You can still transfer tokens instantly, but the token transfer does not, by itself, complete the notarial step that Polish law requires for real estate ownership. So you must define what the token trade really means.

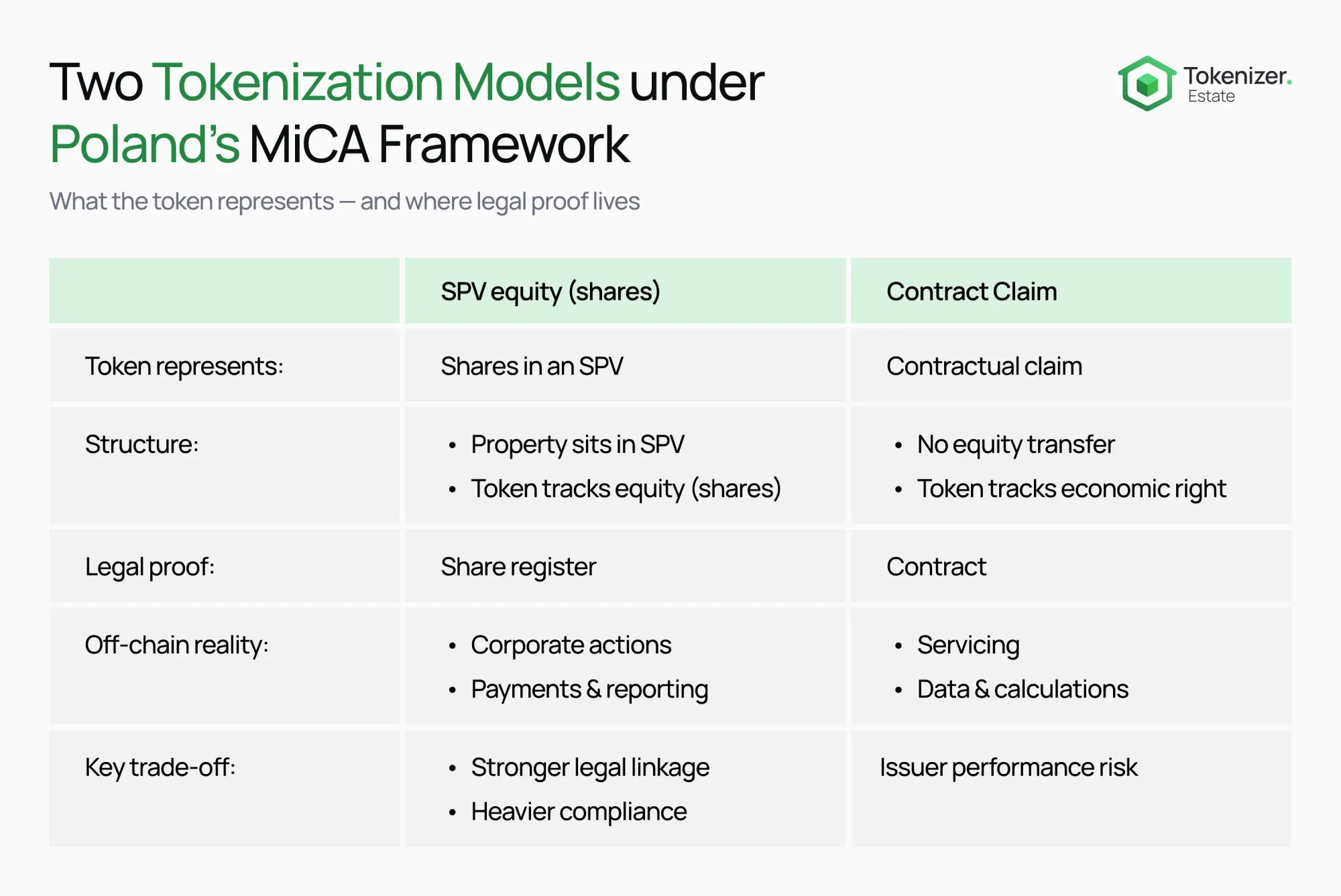

In practice, most “real estate tokens” in Poland become one of two things:

- a token linked to an SPV or holding company that owns the property (so the token reflects a position tied to that structure), or

- a token that represents a contractual claim (loan, profit share, rent-linked entitlement), so you do not pretend the token is the land title.

Both can work, but they are not the same product. The first is a governance-and-register problem. The second is an enforceable-claims problem (and a solvency + servicing problem).

MiFID II vs MiCA in Poland: a quick “regulatory lane” check

Before you decide how to structure a tokenized real-estate product, you need to answer one practical question: is the token a financial instrument (share/bond-like), or a crypto-asset that is not a security? That classification determines which rulebook you’re in. If the token behaves like a traditional security, the MiFID II lane typically applies (and MiCA generally doesn’t). If it’s a non-security crypto-asset, the MiCA lane governs issuance and the services around it (distribution, custody, trading, onboarding).

This matters directly for the two product types above. A token that mirrors SPV shares or bond-style instruments tends to become a governance + register problem under the financial-instrument framework. A token that represents an enforceable contractual claim is often scoped as a MiCA-style crypto-asset, which brings authorisation/notice expectations for service providers and operational duties (including onboarding and controls).

MiCA in Poland: timing that changes product plans

In 2026, tokenization in Poland sits under EU rules as soon as you touch crypto-asset issuance or crypto-asset services. MiCA (Markets in Crypto-Assets Regulation) applies from 30 December 2024, with earlier application for some token categories from 30 June 2024.

This matters once you plan your launch timeline and your “who does what” roles. Even teams with a strong legal structure often get surprised by timing: when a service becomes regulated, when a transition period ends, and what needs to be true before you can scale distribution beyond a small pilot.

A simple planning rule helps: if your model depends on a long “we will fix licensing later” window, you should treat that as a risk, not a plan. Tokenization can be a good way to widen investor reach, but the moment you rely on broad access, you also inherit the need to run eligibility, records, and controls like an adult financial product.

Shares, registers, and “on-chain ownership”: where people get it wrong

Most projects fail because the team treats the token ledger as the source of truth, but the legal system still looks to a register, a securities account, or a contract to decide who is actually entitled. When money, control, or default forces the question, the gap becomes a dispute.

This usually surfaces in three moments.

First, secondary trading. Liquidity sounds like the reason to tokenize, but liquidity only exists if you have a compliant way to trade and a clear method for keeping eligibility rules intact during transfers. If you cannot keep KYC/eligibility aligned with token ownership, restricted buyers can become holders “through the back door,” and you inherit a compliance problem that is hard to unwind.

Second, distributions. Smart contracts do not verify rent rolls, expenses, valuation choices, or allocation logic. Automation pays out fast, but it can spread errors fast too. This is why teams discover too late that the real bottleneck is data quality, auditability, and dispute handling—not the payout code.

Third, governance under stress. Structures that separate economic rights from legal control can look stable in calm markets, but stress creates sharp edges: refinancing, asset sale timing, underperformance, or investor conflict. If holders thought they bought “ownership control” but they really bought “economic exposure,” the conflict tends to appear mid-life, not on day one.

If you are building this as a product (not a one-off deal), the operational layer becomes the real work: onboarding, eligibility, cap table logic, distributions, reporting, and exceptions. This is why many teams use a platform approach to keep those parts consistent over years, not weeks—platform page describes what that operating layer usually includes.

Where tokenization projects in Poland break—and where it helps

Tokenization helps most when the token is tightly mapped to an enforceable right and you can keep the legal record in sync without heroic manual work.

That is why it often works well for:

- products where the token represents a clear contractual claim and you have strong terms + reporting, or

- structures where the off-chain register can be updated reliably and governance is clear.

It breaks when token transfer is treated as legal finality in areas where Polish law still requires a different form (like a notarial deed for real estate) or where the authoritative register is not operationally linked.

If you want a practical sense of the cost buckets that appear once you go beyond a pilot (legal, compliance, tech, ongoing admin), cost guide breaks down the categories that teams typically underestimate.

Conclusion

Do tokenization in Poland only when you can keep the token ledger and the legally decisive record moving together—otherwise you are building tradable confusion, not tradable ownership.

The key moment is usually clear. For a founder, it is a simple choice: is tokenization the real core of the product, or just a modern interface on top of an old structure? For an investor, it is a basic due diligence question: which legal document proves my rights in Poland, and who can protect these rights if there is a problem? And if you are building a platform, you need to decide if you are ready to handle the practical parts — register updates, compliance checks, payouts, and special cases. Like in any industry, tokenization works well only when it is built carefully and follows the law from the start. This is what makes the model stable in the long term.