Tokenization in Estonia: Digital-State Infrastructure for Property RWAs

Estonia’s digital tools can reduce friction, but property rights still depend on registers and legal records. This article shows what a token can represent (shares, cashflows, or a title “mirror”), where legal truth lives, and when tokenization fits—or breaks—in practice.

Real estate tokenization in Estonia in 2026 is not only a “blockchain” choice. It is a choice about what legal right you put into a token, who controls the legal record, and what happens when there is a dispute.

This article is for founders building a tokenized real estate product, asset owners and managers who want a digital issuance, and investors doing due diligence on an Estonian “property token.” It helps with a practical decision: do we tokenize at all, and if yes, what scope is still safe to run in real life.

Tokenization in Estonia 2026: what the token really represents

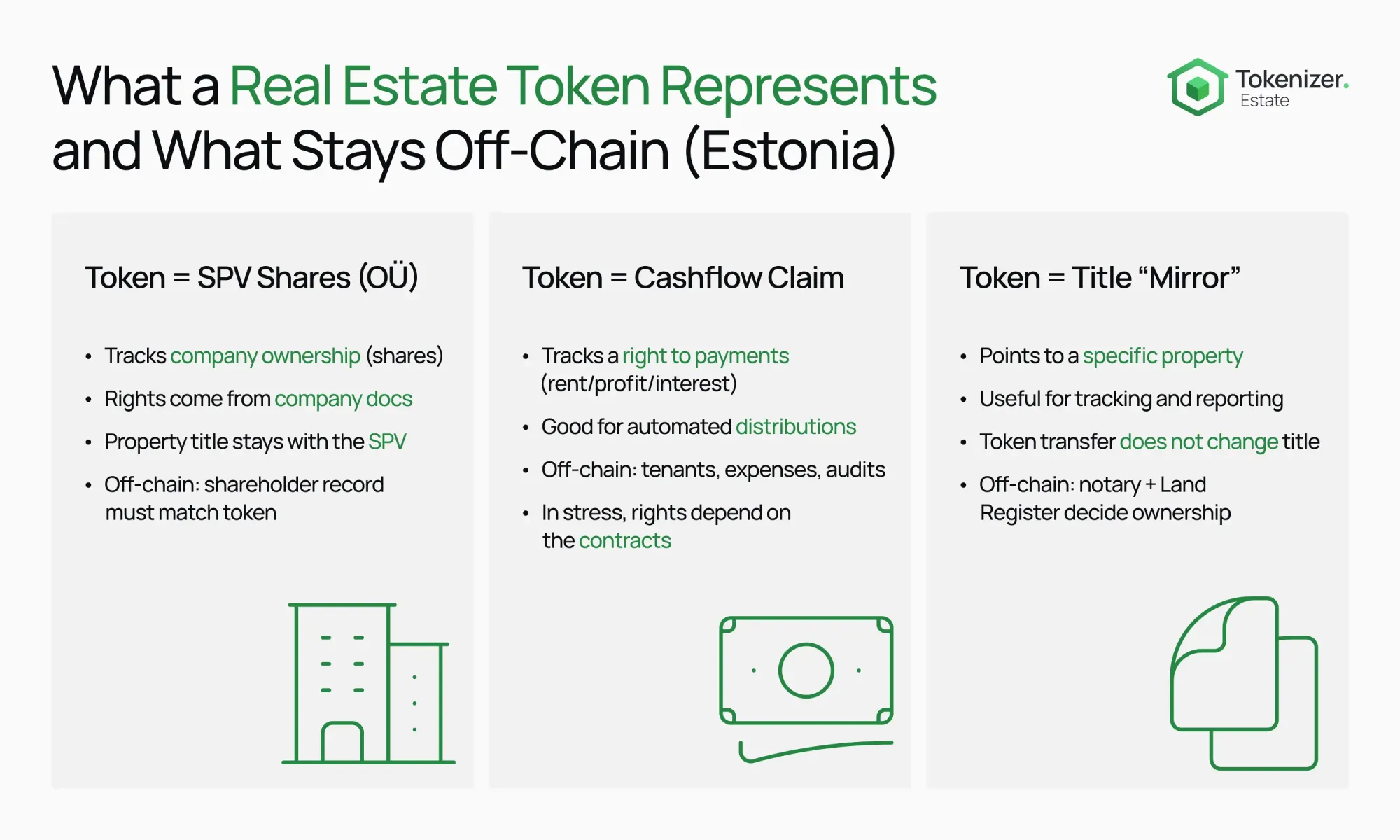

Tokenization means you take an existing right and represent it with a token. The plan is that holding and transferring the token tracks who holds that right. In real estate, the right is usually one of three things: (1) company shares in a property-holding SPV, (2) a contractual claim linked to cashflow, or (3) a “mirror” reference to property title.

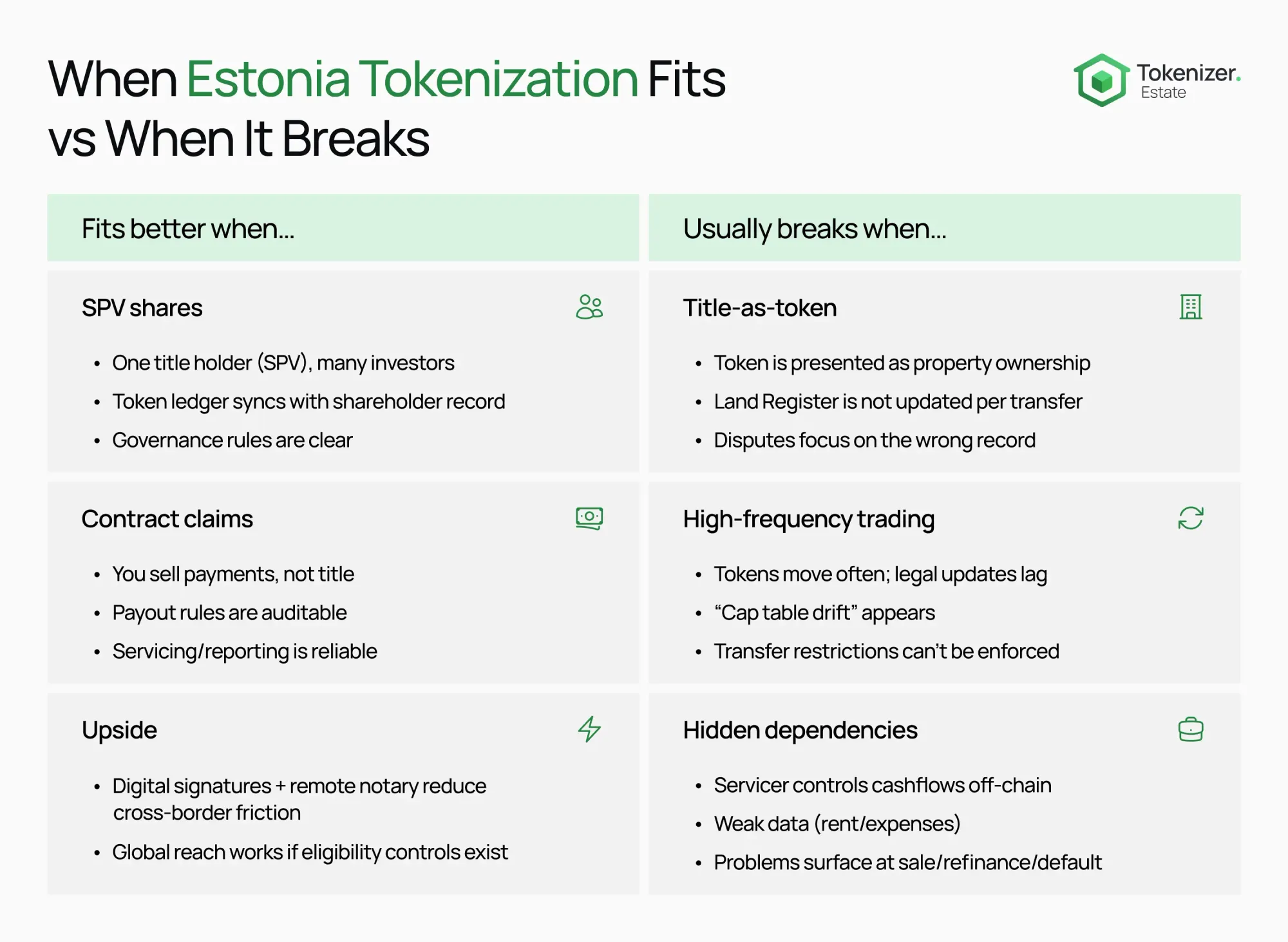

What tokenization does well is make investor reach and administration easier. It can help you accept smaller tickets, serve more holders with fewer manual steps, and support cross-border interest because onboarding and reporting can run as a digital flow. This matters once you want global investor outreach but still need controlled access, clear records, and repeatable operations.

Before we talk about Estonia’s legal limits, it helps to be clear what the token is actually representing.

Estonia is also strong on digital execution. Digital signatures have legal force, and remote notarisation exists, which can reduce the “everyone must be in one room” problem. That does not remove legal steps, but it can reduce friction in cross-border deals where parties are not local.

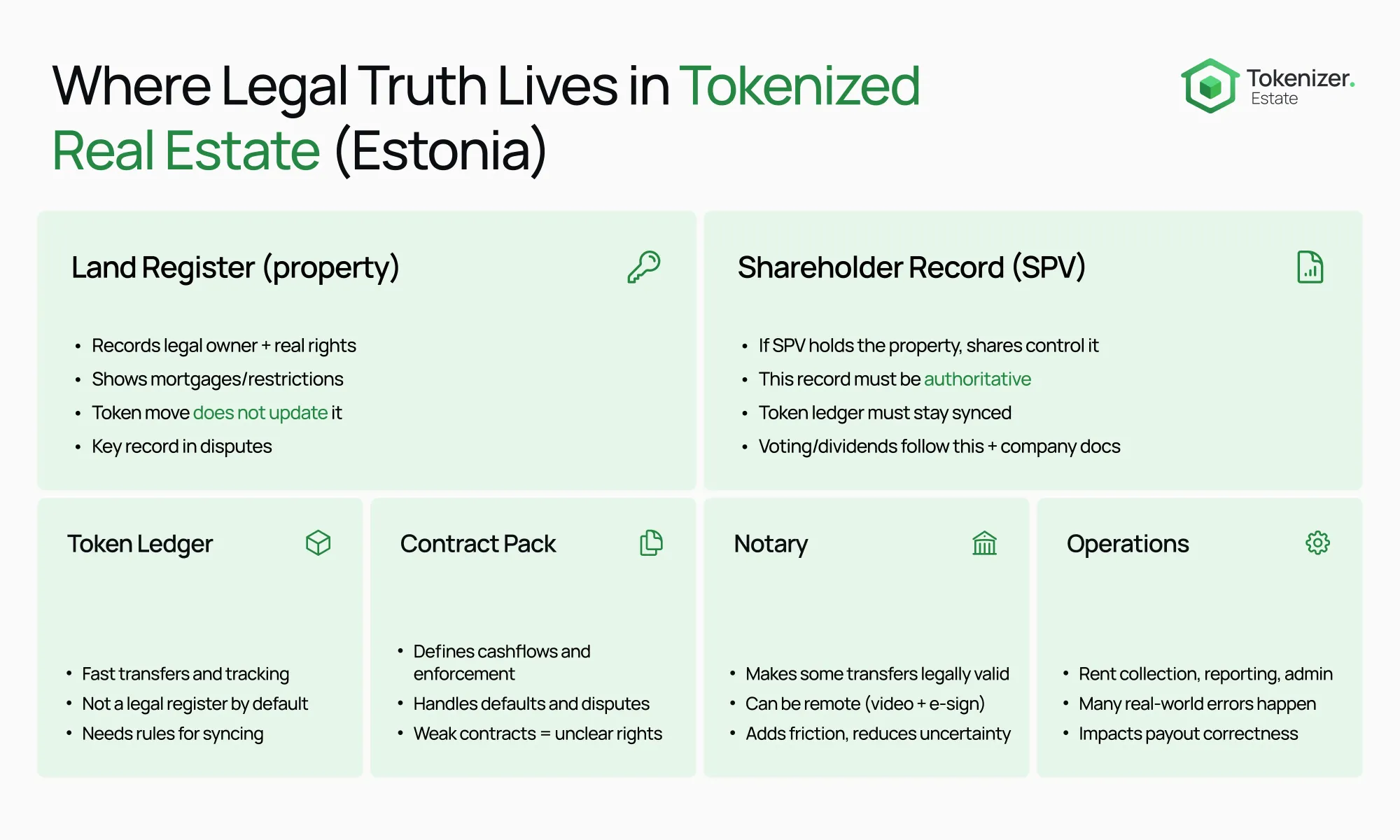

The key point: a token ledger can be perfect, but it may still be non-authoritative. If a court or a counterparty asks “prove my right,” the answer is usually an off-chain record.

Land Register and notary limits in Estonian property tokenization

The first hard limit is property title. In Estonia, ownership and other real rights over an immovable are tied to notarial acts and the land register record. A token transfer does not, by itself, change the land register entry.

For the clean source statement, the Law of Property Act states the rules around transferring and encumbering immovable property ownership and the role of the land register.

This matters once you promise “fast settlement” or active secondary trading. You can trade tokens quickly, but you must define what that trade means in legal reality. Is the token only an economic position? Is it a promise to complete the off-chain step later? Or do you block token transfers until the off-chain record is updated? If you do not decide this early, expectations drift and liability grows.

Because of this, many Estonian “property tokens” become one of two workable models in practice.

One model is an SPV that owns the property, where the token represents shares (or a mapping to shares). This can reduce land-register friction because title stays with one owner (the SPV) while investor ownership moves at the company level. But it creates a new risk: cap table integrity. If the token ledger and the legally maintained shareholder record drift apart, you have a dispute waiting to happen.

The other model is a contractual claim: a loan, profit share, or rent-linked entitlement. This avoids pretending the token is property title, but it changes what investors really own. This usually surfaces later, when a holder learns that “asset-backed” does not automatically mean “secured” in a default scenario.

Regulation and compliance boundaries for tokenized property RWAs in Estonia

In 2026, the most common compliance mistake is not “forgetting crypto rules.” It is misreading what the token is in legal terms.

If the token is effectively a security (for example, share-like or bond-like rights), then it is treated like a security, even if it is issued on a blockchain. Estonia’s financial supervisor makes this point clearly: FSA explains that security token offerings are regulated on the same basis as other securities.

This matters once you plan distribution and investor access. The marketing story often pushes toward “global.” The compliance reality forces you to define who can buy, under what rules, and how you keep eligibility aligned during transfers. If you cannot enforce these restrictions, your “global reach” turns into a regulatory risk, not an advantage.

A numeric point that changes project scope: securities public offers in Estonia can trigger different document requirements based on total consideration, including a prospectus requirement above an EU-wide threshold. This matters when teams think they can “just do small rounds” without planning the 12-month window.

Where tokenized property projects break—and how to scope them so they don’t

Most projects fail because tokens move faster than the legally enforceable record can follow. The result is a gap between “who the token ledger says is the holder” and “who the legal system recognises as entitled,” especially when money, control, or default forces the question.

This usually surfaces in three moments.

First, secondary transfers. Liquidity is often the reason teams tokenize, but liquidity only exists if transfers stay compliant and the authoritative record stays aligned. If restricted investors can receive tokens through the back door, a product issue becomes a compliance issue.

Second, distributions. Automation can pay fast, but it can also spread errors fast. Smart contracts do not verify rent rolls, expenses, reserve policies, or property manager decisions. This is why teams discover too late that the real bottleneck is data quality, audit trails, and dispute handling—not payout code.

Third, stress events. Refinancing, enforcement, or a sale is where “what do I really own?” becomes urgent. If token holders expected ownership control but only bought economic exposure, the conflict tends to appear mid-life, not on day one.

So what changes in practice? The safest scope is usually narrower than the first product idea. Instead of “token = title,” teams do better with “token = shares in a property SPV” or “token = a clear contractual claim,” plus strict rules for how token state stays consistent with legal state.

If you want an example of how teams package the operational layer (onboarding, records, payouts) as a system instead of spreadsheets, platform shows what modules platforms often describe for this job.

Conclusion

Estonia gives real strengths for tokenization: strong digital identity culture, legally valid digital signatures, and remote notarisation that can reduce cross-border friction. These positives matter once you aim for global investor outreach but still need controlled, auditable operations.

At the same time, the core constraint stays: property title and enforceable real rights do not move just because a token moved. If you build as if they do, the mismatch shows up later — when changing course is expensive and often irreversible.

A useful comparison read for scoping discipline is Netherlands case maps where the “legal-mapping problem” is explained in a similar way.

If you only remember one thing, it should be this: Estonia tokenization works in specific shapes — and breaks in others.

The decision moment is usually simple: a founder chooses whether to promise liquidity, an issuer chooses between tokenized equity versus tokenized claims, or an investor asks one question — what exact record proves my right if something goes wrong, and who can enforce it?